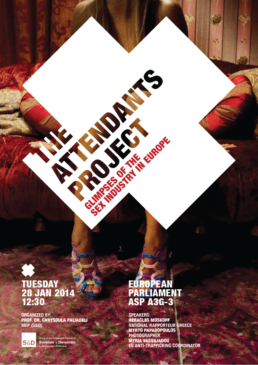

THE ATTENDANTS

When Life Isn’t a Moment

PARTICIPATORY PHOTOGRAPHY, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

Myrto Papadopoulos and Shayna Plaut

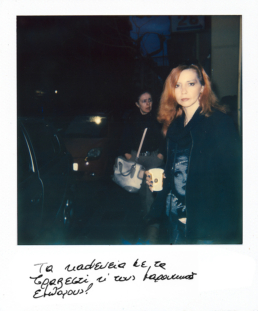

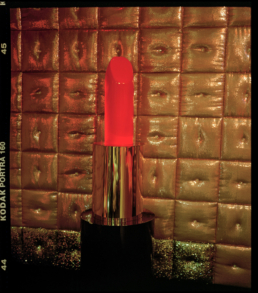

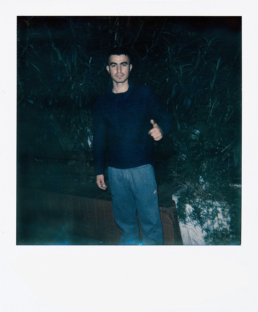

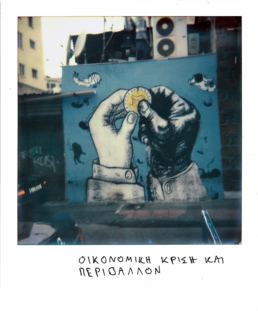

Myrto Papadopoulos is a documentary photographer and filmmaker specializing in intimate longform projects that often involve human rights and social justice, particularly as it relates to people who are too often rendered marginal or invisible. Originally from Athens, Greece, she worked and studied abroad for many years and returned to Greece in 2009, where she began to work intensely for international media. It was a dark time. The financial crisis was escalating, as was an increase in migration – including refugees and those seeking asylum – from Syria, Afghanistan, and subSaharan Africa. There was also a dramatic increase in HIV rates. These ingredients created a toxic cocktail of nationalism, xenophobia, and a search for blame among those on the margins. At the same time, the sex industry that had always existed and was previously fairly lowkey was growing, and becoming more and more multilayered and transnational.

Although sex work has been legal in Greece since 1999, within this increasingly hostile and suspicious environment, political leaders publicly blamed and shamed sex workers on more than one occasion, for everything from increased HIV rates (although there was no correlation), to being foreign (although many, if not all, were Greek themselves), to being evidence of – and contributing to – general societal decline. It is within this context that Myrto began working on a photographic project documenting the booming sex industry in Greece…

THE RADICAL POWER OF EMPATHY– or – WHAT DOORS OPENED WHEN I WAS TOLD “NO”

MYRTO: I went quite deep into this project.

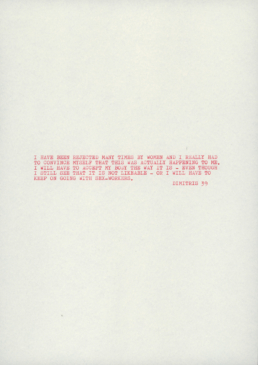

And I understood I wasn’t only in this project as a photographer. I was part of it. I was part of this narrative. After working on it for years, this project also became personal. I was trying to explore a part of my own understanding of sexual morality, the role of women, and sexuality.

Women and sex. Women and violence. Women and sexual assault…

SHAYNA: I’m just wondering, when she said, “No, you cannot take my photo,” what did you learn about yourself? You said you were stopped in your tracks.

Why? Why did you react that way? What did you learn about yourself?

MYRTO: One thing I learned and realized about myself was that I want to go deep. To go deeper with my narratives and with those whom I meet. To go beyond the one-dimensional layer of a story. To search for more than one truth. To push myself and to be more of a thinker and, in turn, to be more accepting of different, sometimes conflicting, truths – even or especially – within one person. Also my interaction – both with the trafficker and with the Bulgarian woman – definitely helped me to be more empathetic. There’s much more to learn and to see and to accept, even – or maybe especially – if you don’t like it. You can work to accept it.

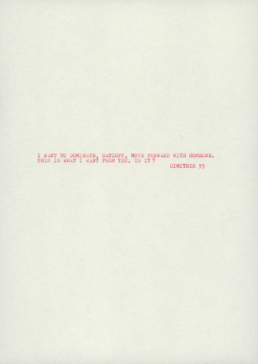

Acceptance is a powerful thing. Empathy is a powerful thing. I also realized that when this woman said “No” that she was reacting to our power to represent and to misrepresent.

We – photographers – can have a massive impact in our society, and it takes a significant level of responsibility from our part to represent someone else’s life, culture, and country. Photographs bring attention: “Photographs of an atrocity may give rise to opposing responses. A call for peace,” as Susan Sontag [2003] described it in Regarding the Pain of Others, but they can also cause great harm. How can the benefit or harm be measured? I don’t know. But visual journalists should continuously study and reflect on their craft and the ethics that guide it. This is what I am always trying to do; however it is a process and not an easy one.

SHAYNA: Now, I’m assuming … I’m assuming that you already thought of yourself as an accepting and empathetic person. So what is new here?

What changed for you? Did this situation make you more accepting and empathetic or …?

MYRTO: I can see the pain in people. However, as I mentioned earlier, I would never carelessly take a picture that would increase someone else’s pain. I saw this woman’s pain – she shared it with me but she didn’t want to share it with anyone else. And I could only respect that, respect the situation she was in…